Claddings – Design Tips

Cladding

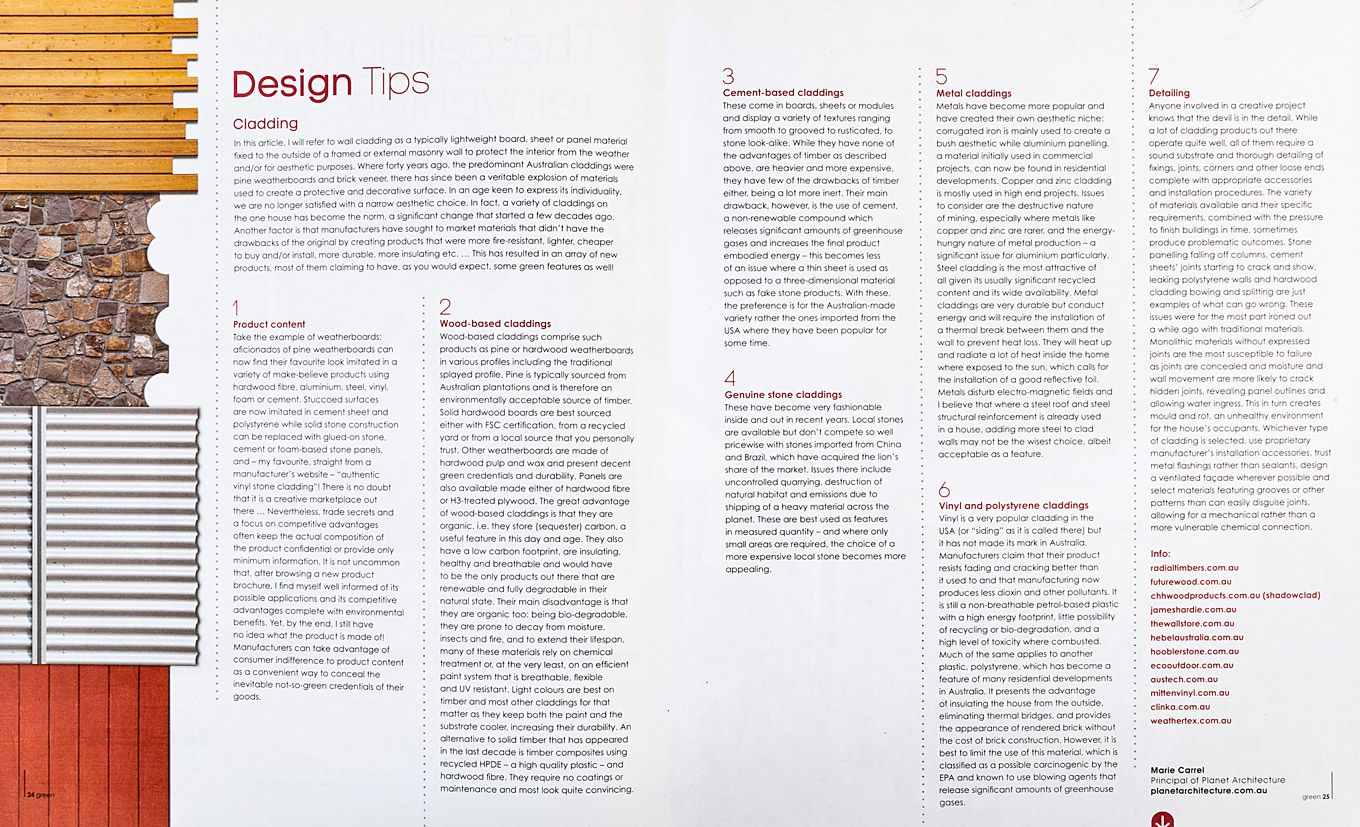

In this article, I will refer to wall cladding as a typically lightweight board, sheet or panel material fixed to the outside of a framed or external masonry wall to protect the interior from the weather and/or for aesthetic purposes. Where forty years ago, the predominant Australian claddings were pine weatherboards and brick veneer, there has since been a veritable explosion of materials used to create a protective and decorative surface. In an age keen to express its individuality, we are no longer satisfied with a narrow aesthetic choice. In fact, a variety of claddings on the one house has become the norm, a significant change that started a few decades ago. Another factor is that manufacturers have sought to market materials that didn’t have the drawbacks of the original by creating products that were more fire-resistant, lighter, cheaper to buy and/or install, more durable, more insulating etc… This has resulted in an array of new products, most of the claiming to be as you would expect some description of green as well!

Product content

Take the example of weatherboards: aficionados of pine weatherboards can now find their favourite look imitated in a variety of make-believe products using hardwood fibre, aluminium, steel, vinyl, foam or cement. Stuccoed surfaces are now imitated in cement sheet and polystyrene while solid stone construction can be replaced with glued-on stone, cement or foam-based stone panels, and – my favourite, straight from a manufacturer’s website – “authentic vinyl stone cladding”! There is no doubt that it is a creative marketplace out there… Nevertheless, trade secrets and a focus on competitive advantages often keep the actual composition of the product confidential or at least discreet information. It is not uncommon that after browsing a new product brochure, I find myself well informed of its possible applications and its competitive advantages complete with environmental benefits. Yet, by the end, I still have no idea what the product is made of! Manufacturers can be known to take advantage of consumer indifference to product content as a convenient way to conceal the inevitable not-so-green credentials of their goods.

Wood-based Claddings

Wood-based claddings comprise such products as pine or hardwood weatherboards in various profiles including the traditional splayed profile. Pine is typically sourced from Australian plantations and therefore an environmentally-acceptable source of timber. Solid hardwood boards are best sourced either with FSC certification, from a recycled yard or from a local source that you personally trust. Other weatherboards are made of hardwood pulp and wax and present decent green credentials and durability. Panels are also available made either of hardwood fibre or H3-treated plywood. The great advantage of wood-based claddings is that they are organic, i.e. they store (sequester) carbon, a useful feature in this day and age. They also have a low carbon footprint, are insulating, healthy and breathable and would have to be the only products out there that are renewable and fully degradable in their natural state. Their main disadvantage is that they are organic too: being bio-degradable, they are prone to decay from moisture, insects and fire, and to extend their lifespan, many of these materials rely on chemical treatment or at the very least, on an efficient paint system that is breathable, flexible and UV resistant. Light colours are best on timber and most other claddings for that matter as they keep both the paint and the substrate cooler, increasing their durability. An alternative to solid timber that has appeared in the last decade is timber composites using recycled HPDE – a high quality plastic – and hardwood fibre. They require no coatings or maintenance and most look quite convincing.

Cement-based claddings

These come in boards, sheets or modules and display a variety of textures ranging from smooth to grooved to rusticated, to stone look-alike. While they have none of the advantages of timber as described above, are heavier and more expensive, they have few of the drawbacks of timber either, being a lot more inert. Their main drawback however is the use of cement, a non-renewable compound which releases significant amounts of greenhouse gases and increases the final product embodied energy – this becomes less of an issue where a thin sheet is used as opposed to a three dimensional material such as fake stone products. With these, prefer the Australian-made variety rather the ones imported from the USA where they have been popular for some time.

Genuine Stone Claddings

These have become very fashionable inside and out in recent years. Local stones are available but find it hard to compete price-wise with stones imported from China and Brazil which have acquired the lion share of the market. Issues there include uncontrolled quarrying, destruction of natural habitat and emissions due to shipping of a heavy material across the planet. These are best used as features in measured quantity – and where only small areas are required, the choice of a more expensive local stone becomes more appealing.

Metal claddings

Metals have become more popular and have created their own aesthetic niche: corrugated iron is mainly used to create a bush aesthetic while aluminium panelling, a material initially used in commercial projects can now be found in residential developments. Copper and zinc cladding is mostly used in high end projects. Issues to consider are the destructive nature of mining, especially where metals are rarer like copper and zinc, and the energy-hungry nature of metal production – a significant issue for aluminium particularly. Steel cladding is the most attractive of all given its usually significant recycled content and its wide availability. Metal claddings are very durable but conduct energy and will require the installation of a thermal break between them and the wall to prevent heat loss. They will heat up and radiate a lot of heat inside the home where exposed to the sun, which calls for the installation of a good reflective foil. Metals disturb electro-magnetic fields and I believe that where a steel roof and steel structural reinforcement is already used in a house, adding more steel to clad walls may not be the wisest choice, albeit acceptable as a feature.

Vinyl and polystyrene claddings

Vinyl is a very popular cladding in the USA (or siding as it is called there) but it has not made its mark in Australia. Manufacturers claim that their product resists fading and cracking better than it used to be and that manufacturing now produces less dioxin and other pollutants. It is still a non-breathable petrol-based plastic with a high energy footprint, little possibility of recycling or bio-degradation, and a high level of toxicity where combusted. Much of the same applies to another plastic, polystyrene, which has become a feature of many residential developments in Australia. It presents the advantage of insulating the house from the outside, eliminating thermal bridges, and provides the appearance of rendered brick without the cost of brick construction. However, it is best to limit the use of this material classified as a possible carcinogenic by the EPA and known to use blowing agents that release significant amounts of greenhouse gases.

Detailing

Anyone involved in a creative project knows that the devil is in the details. While a lot of cladding products out there operate quite well, all of them require a sound substrate and thorough detailing of fixings, joints, corners and other loose ends complete with appropriate accessories and installation procedures. The variety of materials out there and their specific requirements combined with the pressure to finish buildings in time, sometimes produce problematic outcomes. Stone panelling falling off columns, cement sheets joints starting to crack and show, leaking polystyrene walls and hardwood cladding bowing and splitting are just examples of what can go wrong. These issues were for the most part ironed out a while ago with traditional materials. Monolithic materials without expressed joints are the most susceptible to failure as joints are concealed and moisture and wall movement are more likely to crack hidden joints, revealing panel outlines and allowing water ingress. This in turn creates mould and rot, an unhealthy environment for the house occupants. Whichever type of cladding is used, use proprietary manufacturers installation accessories, trust metal flashings rather than sealants, design a ventilated façade wherever possible and select materials featuring grooves or other patterns than can easily disguise joints, allowing for a mechanical rather than a more vulnerable chemical connection.